|

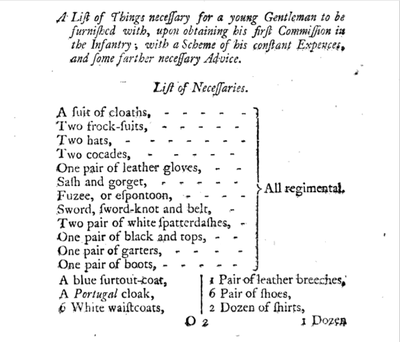

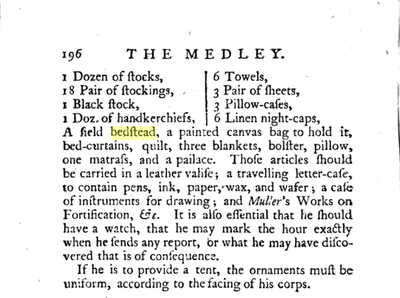

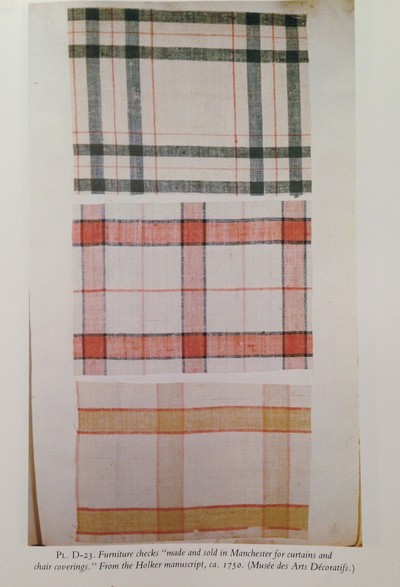

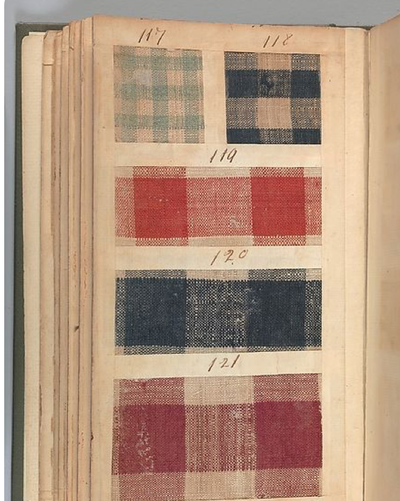

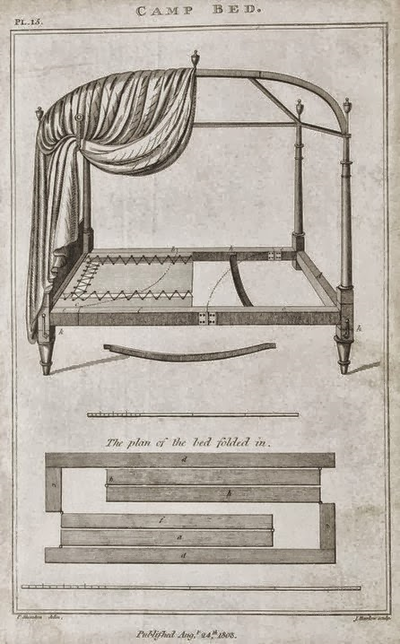

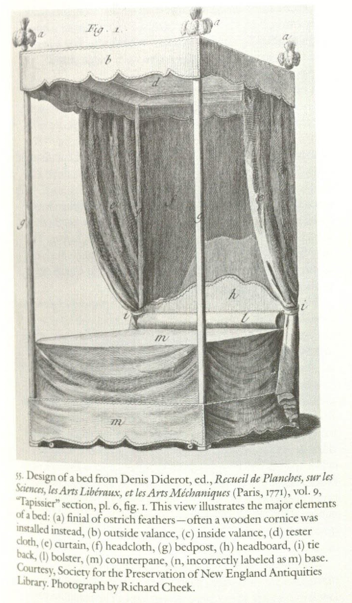

This past year, my focus has been updating some of the older textiles that we have around the Old Barracks Museum— particularly in the one of the officer’s rooms. Our field bed has been bare for so long and I often got statements from visitors such as “why would they sleep in that?” This is the opposite of the response you want to get from visitors having just seen the sparse nature of the enlisted men’s bunks. By updating the current textiles of the Ensign's room and eventually other rooms, we can now more effectively emphasize class distinctions in the British Army, not only between higher and lower ranking officers, but also between commissioned and enlisted men. The 1768 The Military Medley by Thomas Simes lists a "field bedstead"in “A List of Things necessary for a young Gentleman to be furnished with, upon obtaining his first Commission in the Infantry." Fabric Selection I decided to make these hangings from blue and white linen furniture check. A number of considerations went into this fabric selection. According to George Hepplewhite in 1794, “[ bed hangings] may be executed of almost every stuff which the loom produces.” The most common fabrics used before the American Revolution were worsteds such as moreen, harateen, cheney, camlet, and serge. More expensive worsted were damasks, which could be made from a combination of wool and silk. Prints and Checks were second in popularity in Boston. Furniture check, largely manufactured in Manchester, was particularly popular beginning in the 1750’s. It was characterized by its bolder pattern, typically a one or two inch check (up to four inches) and large white field. It could come in many sizes and colors including blue, green, yellow, scarlet, and crimson (Figures 3-6). A 1762 journal entry by James Boswell in London specifically mentions his field bed with check curtains: “ a handsome tent-bed with green and white check curtains [which] gave a snug yet genteel look to my room, and had a military air which amused my fancy and made me happy.” Towards the latter half of the 18th century and into the 19th century, use of linens such as furniture check and printed cottons increased, often for the ease of washing. Furniture check seemed the most appropriate for the ensign’s bed hangings. It was particularly popular in the 1750’s. The check linen is also be washable and therefore more suitable for military life. Simes even mentions the importance of washing one's bed furnitures while in barracks, suggesting that the officers had hangings of washable fabric: In addition, the check linen hangings are more appropriate for the social and economic status of the young ensign. Bed hangings were often the most expensive item in a home due to large quantity of fabric required and the cost of imported cloth. Due to this cost, bed hangings and the quality of the fabric reflected the social status of the owner. Although the lightweight check linen may not seem the most appropriate for an Officers’ House in the winter, keeping linen on the field bed helps reflect the status of the young officer. He may not be wealthy enough to have both summer and winter curtains, which would only be seen in more affluent houses. Construction Considerations The field bed in the Officers’ House has a unique shape compared to many extant field beds, which typically have a curved arch canopy such as the one illustrated in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary. Instead, the bed in the ensign’s room has a raised, flat canopy like a four poster bedstead illustrated by Diderot. Due to this unique shape, I had to construct the hangings with consideration to the unique to the frame of the bed. incorporating aspects of both domestic bedsteads and field beds. Bed Furniture A complete set of furniture for a typical full sized bedstead includes valences, four curtains which encircle the bed and reach the floor, head cloth, tester, and bedspread. Valences Valences are commonly ten to twelve inches deep and are composed of three pieces, one for each side and one for the end of the bedstead. Valences may be unlined or lined with linen or buckram and may be shaped or straight. They can be attached by folding lining material over and piercing at intervals with eyelet holes which hang from hooks in the tester frame. Including valances using this method on the ensign’s bed was problematic since there are no hooks on the frame. In addition, the 1803 Sheraton Dictionary image does not show valences on the field bed, because the canopy is curved. Curtains Curtains on four poster beds were typically suspended using 3/8th inch wide tape made into loops two inches in length. These are spaced five to nine inches apart and sewn to the reverse side of the curtain. A tape along the edge of the top of the curtain is sewn over these loops. These are then “tag tied” around brass rings about one inch in diameter, which are oval in section, or flat. Curtains may be tied back using a loop of matching material hooked around a button (Figure 11). Again, hanging the curtains in this manner did not work because their are no hooks on the current ensign’s bed. One method of attaching curtains without hardware is to drape them. Samuel Grant, an upholster operating a shop in Boston in the mid 18th-century offered hangings for portable field beds designed to drape over the tester frame. This draping method made sense for our bedstead as it is more convenient and quick to set up rather than attaching the valance to the frame with iron tacks. Additionally, in his descriptions of four field beds, Chippendale mentions that the “furniture [i.e. hangings],... is made to take off.” Head Cloth The head cloth hangs flat and falls to just below headboard. Tester Cloth The tester cloth is the canopy that covers the top of the bed. Due to the typical 20-36 inch width of fabric being manufactured on looms in the 18th-century, it is composed of two pieces with a seam down the middle width-wise. What's Next? Now that the hangings are done, the next step is the rest of the bed furniture! My goal is to have this field bed completely furnished with ticks, sheets, blankets, bolsters etc.—items fit for an officer. Thank you so much to the many hands that helped sew at the British Occupation event! Sources

Cummings, Abbott Lowell. Bed Hangings, A Treatise on Fabrics and Styles in the Curtaining of Beds, 1650-1850, 3rd ed. Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1994. Jobe, Brock. “The Boston Upholstery Trade, 1700-1775.” In Upholstery in America and Europe from the Seventeenth Century to World War I, edited by Edward S. Cook, 65-89. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987. Montgomery, Florence M. Textiles in America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1984. Nylander, Jane C. “Bed and Window Hangings in New England 1790-1870.” In Upholstery in America and Europe from the Seventeenth Century to World War I, edited by Edward S. Cook, 175-185. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987. Simes, Thomas. The Military Medley, 2nd ed. London, 1768. “The Comforts of Home: Camp Equipage of the Commissioned Officer During the American War for Independence.”The 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center. July 2017.

0 Comments

I recently knit a reproduction of a silk "Long Purse" c.1700-1750 from the Snowshill Wade Costume Collection, NT 1349539 Original "Long Purse"

|